Preserving the "Culture" in Urban Agriculture

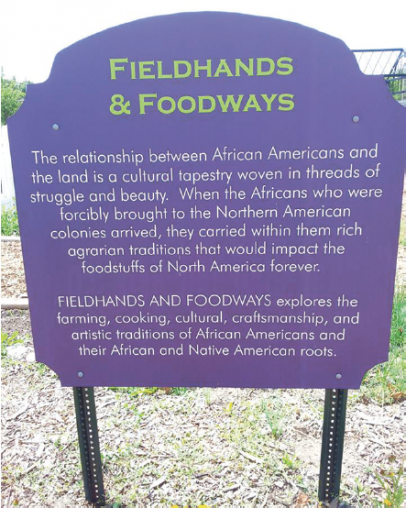

On one of the most humid days of this year’s growing season, with the thermometer topping out at 95 degrees, I kneel in a small plot planting okra, sorghum, and cowpeas. The plot is one of many at Alice’s Garden, a two-acre community garden and urban farm in central city Milwaukee. A teenage Hmong staff member has turned over the soil, and as she passes me seeds, we embark on a conversation about the crops our different ancestors have grown for generations. We discuss how we honor those ancestors by never forgetting the sacredness of land and food. (Well, really, I am convincing her of its importance.) We are in the FIELDHANDS AND FOODWAYS area of Alice’s Garden, a project designed to provide a visual platform for conversations and education about race, history, culture and foodstuffs. We are planting in the Huck Patch, a demonstration slave garden. The dialogue turns to ethnobotany, herbal medicine, and ethnic cooking. As we both share stories of the history of our people, and what we know of our families’ farming and culinary traditions, it is clear the culture has been awakened in urban agriCULTURE.

We have entered a time in this country where community gardens are popping up like daffodils in early spring, offering signs of new life within inner-city terrains that sat void for years, even decades. As the landscape of American cities is sprinkled with these neighborhood treasures, many are created to impact food deserts, promote healthy food access, reconnect city folk to the natural environment and one another, and serve as a springboard for neighborhood development. What tends to be overlooked is the cultural connections people have with cultivating land and growing food. In neighborhoods where people of color comprise the dominant presence, organizers of communal gardens must begin to facilitate efforts that encourage a deeper understanding about our history and relationships with the land and food.

It is easy to create a garden on a city block that invites neighborhood children to grow carrots, lettuce, beans, tomatoes, and to engage them in other forms of environmental education. I’ve done it several times over. However, if the urban agriculture movement is going to be sustained in Milwaukee and other cities, we must reach deep into the agriCULTURAL history represented by the families on those blocks, and within the crops we choose to plant, and invite to the community garden table the very real tales of struggle and injustice related to growing food throughout the world and in this nation’s soil. We must be willing to hear the refugee story of being forced from the homeland, seeking solace in the hills or fleeing to a foreign land. We cannot plant a Three Sisters Garden, and then choose not address the history and continued disrespect of American Indians’ rights to land. Let us not teach an African-American child to plant a watermelon from seed without helping them to understand the cruel stereotypes associated with their ancestors and this fruit.

As painful as the storytelling may be, the stories must never stop being told. When I give tours of the FIELDHANDS AND FOODWAYS project, there are often visitors who are uncomfortable, if not startled, by the presence of the Master’s Kitchen Garden. Framed by a white picket fence that stands out from the other plots, from a distance people are drawn to it. As they get closer and read the signage associated with that particular garden, I often see the lump develop in their throats. There are rental gardeners at Alice’s Garden who cannot call it by name. Yet, as the country erupted with strained dialogue about the sentiments expressed by celebrity chef Paula Deen, and her daydreams about going back to a time when many of my ancestors were in bondage to and serving hers, I sought out the visual reminders of how things used to be displayed in the FIELDHANDS AND FOODWAYS gardens. It is in that space that I forgave this woman, whose recipes have nourished and satisfied my family. I forgave her for being a product of generations of agricultural racism. It is in that space where many come face-to-face with a troublesome, bitter history of growing food that built this nation.

Indeed, the culture in urban agriCULTURE is not just one of historical burden. It is also filled with rich agrarian and culinary traditions. Urban agriculture provides an opportunity to celebrate food and people, creating bridges of understanding that often happens when people gather to explore food or share meals. The gift of the immigrant is present from field to fork. Greek, Ethiopian, Korean, Italian, Mexican, Thai, Irish, Palestinian, Jamaican, Chinese cuisine all pepper the American palate. A crop of “Irish potatoes” opens a door of learning about both the Irish potato famine and the stereotypes of Irish Catholics in the 19th century, and at harvest time may culminate with an Irish feast of potato, cabbage, carrot, turnip and apple dishes. Tomatillos, first grown by the Aztecs as far back as 800 B.C. and popular in Mexico and other Latin American countries for centuries, have made their way to small plots in Milwaukee community gardens. The diversity of the plant itself produces intrigue even before our Mexican friends teach us how to make salsa verde. Planting the popular Thai chili pepper, prik kee noo, provides a venue to talk about companion planting, the history of Thailand, and grants an invitation to welcome a local Thai chef to the garden. Fava beans, brought to Alice’s Garden by a native of Western Asia and one of the oldest plants in cultivation, once eaten in Ancient Greece and Rome, stir conversations about both religion and recipes.

Where traditional American agriculture at times feels monolithic in its representation of farmers and crops, urban agriculture caters to endless possibilities of diversity in people, plants and programs. It lays the groundwork for community gardens and urban farms to be abundant in both the food and cultures that are tended.