Kitchen Colored: The Accessible Alchemy of Natural Dyes

Your kitchen is full of color. Onion skins, red cabbage, coffee, turmeric and beets are among the common food items that can transform plain white eggs into colorful Easter showstoppers. But more than just color, these natural dyes provide a direct link with thousands of years of human history.

Natural dyeing was commonplace little more than a century ago, used for clothing, textiles, food, art and cosmetics. The development of synthetic dyes in the late 19th and early 20th centuries made it possible to create virtually any color on the color wheel, anywhere in the world. Deriving color from natural sources became virtually a lost art.

Artist and designer Sarah Eichhorn grew up, as she says, a “big environmentalist.” But she never connected her interest in textiles to sustainability until college, where she studied fashion and costume design.

“The idea of dying fabric with plants blew my mind,” says Eichhorn, who co-chairs the Fashion Department at Mount Mary University.

Eichhorn really started paying attention to plants while working as a gardener in Chicago after college. It was the perfect combination of her background in textiles and her growing knowledge of native plants.

“Looking at and working with plants made me think about their potential for dyeing,” says Eichhorn.

Some dye materials like walnut and sumac produce strong, durable colors on their own. These are called substantive or direct dyes. Others need the addition of a mordant to form a durable bond. Mordants allow the dye to chemically bind to the fabric or other material. Some mordants, like copper and iron, can also change the color of the dye, making it brighter or duller. Every dye is different—one type of mordant won’t do the same thing to every single dye.

“So much of dyeing is experimenting,” explains Eichhorn. “What time of day you harvest, the freshness of the materials, how hard the water is ... These are all things that can really change your dye.”

That variability is part of the charm of natural dyeing, but also part of what drove the rise of synthetic dyes.

Transforming common plants into beautiful color is an accessible alchemy: Fill a pot with water, add leaves (or nuts or seeds or bugs), throw in a square of fabric, bring it all to a simmer and wait for the magic. Just like local food (the source of many colors), the most common dyes came from nearby, so the yellows of one area could differ from the yellows of another region. In a world flush with every color, it can be hard to imagine a past where color denoted geography, class and power.

For centuries, bright colors were highly desirable and largely out of reach for everyone but the rich and royal. Hard to find colors, particularly purple, became markers of status.

Tyrian purple, also known as Royal or Imperial purple, came from the crushed glands of the murex mollusk found on the east coast of the Mediterranean. Based on the quantity of shells found in the area, some historians estimate that it took between 8,000 and 10,000 shellfish to produce one gram of dye, making it quite literally worth more than gold, and thus accessible only to the most wealthy. The Phoenicians gained great fame as manufacturers of purple in the ancient world.

One of the most important and widely used natural dyes came from the root of the flowering perennial Madder (Rubio tinctorum, a scientific name that comes from tinctorius for dyeing or staining). Ground into a powder, madder root produced a brilliant red used by Persians, Egyptians, Greeks, and pretty much everyone until the 20th century.

“Any red you see in medieval tapestries is madder root,” says Eichhorn. “It has such a long history and appears in cultures around the world.”

Madder root gave the red in the American flag that inspired Francis Scott Key to write our national anthem. The blue field beneath the undyed white wool stars came from indigo, likely from South Carolina where the indigo plant was a staple crop.

European settlers brought their own experience with dye plants and learned from Native Americans. Roots, nuts, flowers, minerals and animals were all sources of color.

The first synthetic dye was discovered by accident. English chemist William Perkin began looking for a synthetic form of quinine for the treatment of malaria at the Royal College of Chemistry in London in the 1850s. The natural form came from the bark of the cinchona tree, which only grew in South America and was in short supply. With English soldiers dying in India, the British were desperate for another source.

Experimenting with coal tar in his home laboratory, Perkin discovered that the substance had turned a rich purple color. He dipped silk in the purple liquid and discovered that the color didn’t run or fade. He called the color mauveine, or mauve. Perkin saw the potential in his unexpected dye pot and left school to open his own synthetic dye factory.

After Perkin’s discovery, Germans invested heavily in the production of synthetic dyes. By World War I, Germany supplied 90 percent of the dyes used in the American textile industry.

Artificial dyes are cheaper, brighter, and more stable, but at a great cost. The chemicals involved—aromatic solvents, formaldehyde, chlorine bleach—wreak havoc on the environment and the health of textile workers.

By the late 19th century, a pharmacy in Waukesha advertised the ease of its synthetic dyes for Easter. “There was a time when the approach of Easter aroused more or less foreboding,” read the 1897 ad. “Colored eggs caused so much fuss and trouble. It’s different now. Dyeing eggs with the dyes we sell is a very easy matter. Brilliant and harmless colors and simple to use.”

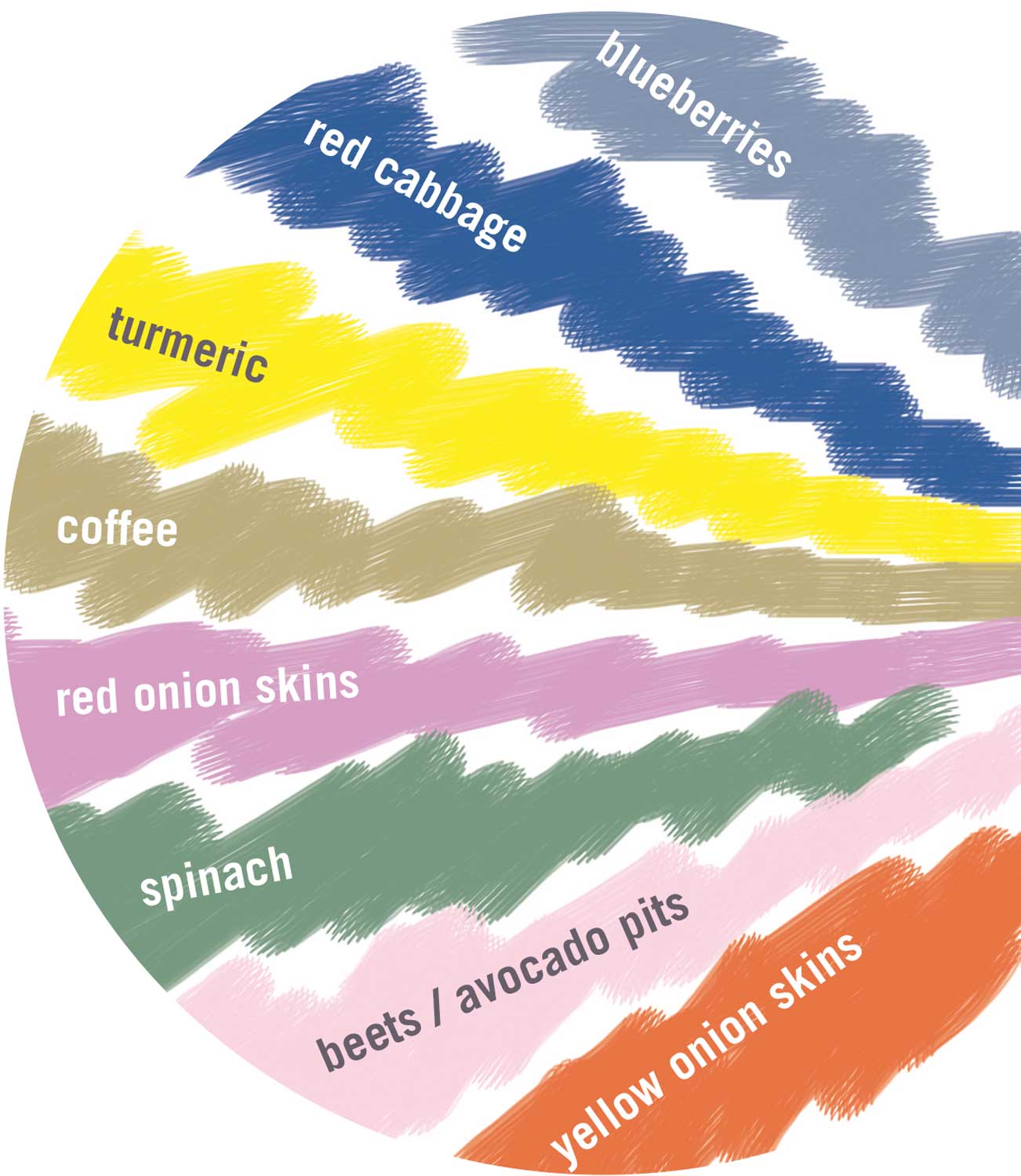

But Easter eggs are, in fact, a great place to start with natural dyes, especially since some great colors are likely lurking in your fridge. Vinegar helps the color attach to the surface of the eggs (by lowering the pH of the dye) and creates vibrant colors. Purple cabbage, for instance, makes blue on white eggs and green on brown eggs. The same beets that stain your hands pink will do the same to your eggs. Avocado pits yield a surprising peachy pink.

“Onion skins are foolproof and look amazing,” says Eichhorn. “They turn linen, cotton, wool and eggs a brilliant bronze-y red.”

Eichhorn’s immersion in natural dyes coincided with the growing maker scene in Milwaukee and wider consumer interest in origins—of vegetables, of meat, of the clothes we wear. People are signing up for workshops and classes like those taught by Eichhorn and others, like Milwaukee designer, Jamie Lea Bertsch, to get back in touch with making and doing.

“There’s a whole group of people who like to have tactile experiences,” says Eichhorn. “And more places keep popping up to offer things that are locally sourced and locally raised.”

Eichhorn is working to establish her own dye garden at her house and to raise awareness of sustainability in fashion. She tries to source her fiber locally as well.

“I can order dyes, but I like the local connection between my textiles and what’s special about here,” says Eichhorn.

The upper Midwest is particularly strong in yellow and orange dyes. These have traditionally been the most common colors produced through natural materials.

One of Eichhorn’s favorite local plants is Goldenrod, which makes a pretty yellow-green color from its late summer blooms. The plant is common and often overlooked, which makes it a great candidate for natural dyes.

“There’s something special about using plants for dyes,” says Eichhorn. “It ties you to not only what you are making but also to the materials, the process, and the seasons.”

Natural Egg Dyes

Here’s a handy guide to get you started—but have fun trying other things. If it’s brightly colored and stains your fingers or cutting board, chances are it will stain your eggshells as well!