Hartland Organic Family Farm: Seeding and Feeding A Community

Driving out to the Hartland Organic Family Farm is like traveling back in time. I was raised out in this neck of the woods, forty minutes west of Milwaukee—or a million miles away, depending on how you measure these things. A two-lane road winds through the forest on the back of a ridge that was carved by glaciers at the end of the last Ice Age. The farm I’m visiting is a throwback, too, to a time when the work of brewers and farmers was closely linked. It’s a family farm, not a factory farm, where Meghan and Tom Findley are turning a couple of hoop houses and a lot of worms into a plan for improving the world we share.

The average age of farmers in the U.S. is 58, but the number of young farmers is on the rise. The Findleys are among this growing number, but Meghan laughs when she says, “Neither of us thought we were going to be farmers!” The way she tells their journey into farming, I can almost feel the hand of fate moving the pieces together. It all started when Meghan was on maternity leave from her job as a schoolteacher. “I was hanging around the house more, talking to Tom, who… was really drawn to Will Allen’s work,” she said, quickly filling in details of how Growing Power, Allen’s Milwaukee-based organization, creates healthier communities through local, sustainable, nutritious food.

Growing Power’s mission resonated with Tom, who kept bringing it up in conversations, and an idea took root in the Findleys’ joint imagination. It went from being a passive daydream to the blueprint for the next chapter of their life together. Tom couldn’t have hoped for a better partner than his wife, a self-proclaimed “save the Earth person,” passionately interested in reducing the amount of waste that ends up in our landfills.

Tom and Meghan took Allen’s beginner-level course in Commercial Urban Agriculture, and learned the basics of farming. The most basic thing about farming is the importance of soil quality. It makes sense that the soil in the city would need assistance, but out in Lake Country?

Although the land the Findleys inherited through Tom’s family had been used as farmland, the 1980’s were an era of heavy pesticide use and chemical fertilization. This rendered the soil less-than-desirable to the new farm family. They want to grow nutritious food in the best possible medium, and the land they inherited just didn’t measure up.

Growing Power taught them two important things: how to knit together a community around food production, and how to improve soil quality through vermicomposting. Composting without worms takes a long time, but this technique puts worms to work, hastening and improving compost. There was a house on the land they inherited, and its fortuitous design makes it perfect for the Findleys’ worms to do their work, producing some of the most gorgeous, rich, velvety soil you will ever see.

The day I arrived, Tom had just returned from Good Harvest Market with large, heavy bins of past-perfect produce. Meghan pointed this out as we walked up a ramp from the garage, down a wide corridor to the elevator. The original owner of the house had been in a wheelchair, and the home’s design accommodations make their farm work possible. Large loads and heavy bins would be prohibitively difficult to maneuver in any typical residential design.

The basement of the home is now full of large, wooden, open-topped cubes full of compost, and worms. When the Findleys were starting out, they built these worm bins, and established relationships with community partners to sustain the worms. The idea was, and is, to keep food waste out of landfills, repurpose it, and turn it into a medium for growing produce. “At the time, Good Harvest Market was the only successful, organic grocery,” Meghan said, making it a natural source for vegetal waste. Still inspired by the Commercial Agriculture class, she eagerly approached the Good Harvest Market and formed their first community partnership.

The Delafield Brewhaus was a sensible second stop because spent beer grains still contain lots of nutrients, plus, Meghan used to work there (and full disclosure: I still work there). Brewmaster John Harrison had been giving all the nutrient-rich, spent beer mash to a cattle farmer as feed for her cows, but agreed to divide his grains to support the brand-new Hartland Organic Family Farm. Local coffeehouses and landscapers provided the remainder of the ingredients for their successful vermiculture. All of this cast-off material could find its way into the trash, but “…they choose to share it with us, which is pretty terrific,” Meghan says.

After the worm beds were built and filled, neighborhood worms voluntarily moved in, even before the Findleys introduced the red wigglers (Eisenia foetida) they bought from Growing Power. Once the worms got to work, the Farm had the medium they needed to begin farming, the next stage of the community food cycle.

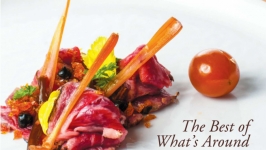

Today, the Hartland Organic Family Farm is best known for microgreens, which are basically superpowered seedlings. Older than sprouts, but younger than baby versions, microgreens are a small, tender stalk and the first few leaves. These plants first started getting attention from chefs in the 1980’s. One look at the Farm’s Red Rambo radish or Red Russian kale microgreens could show you why they are traditionally prized as a visual and flavor component, but these little plants are now getting a second look for their nutritional benefit. A recent study from the Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry reported that microgreens contain four to six times more nutrients than mature leaves of the same plants. Although more research will be necessary to confirm these findings, these results sound promising.

The microgreens represent the final stage of the food cycle, and the realization of the Findley’s dream: food waste from the community is recycled at the farm, turned into healthy soil, and used to grow fresh, sustainable, nutritious produce for the community. “It’s what we can do together, to make everybody better,” Meghan says.