Not Just Nostalgic

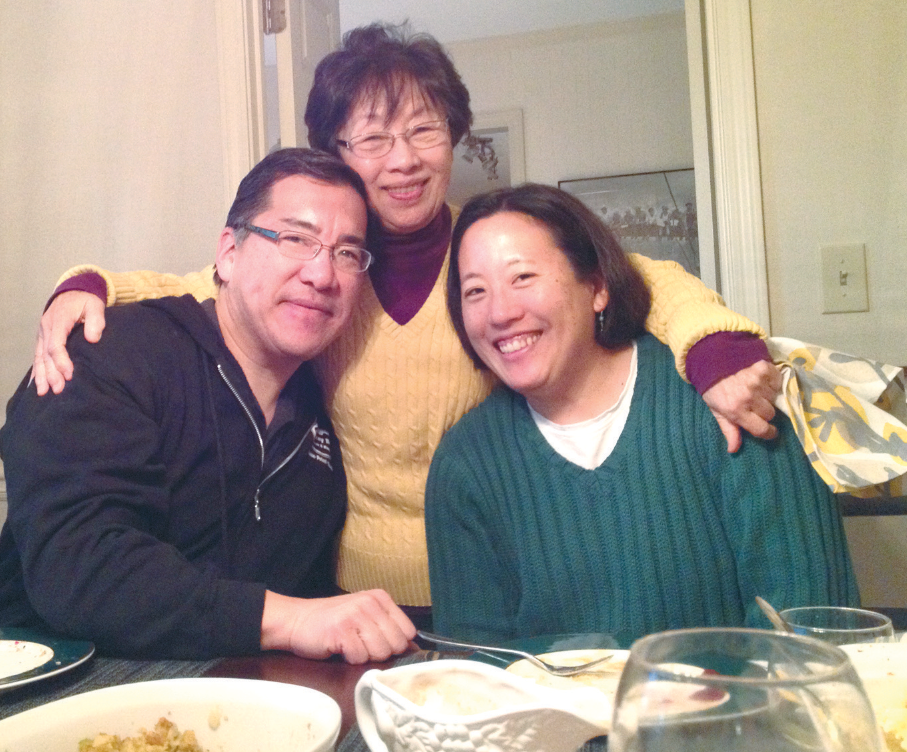

Last year I celebrated Thanksgiving at my sister’s house for the first time. Like many of you, I ate a light breakfast and skipped lunch in anticipation of the mid-afternoon feast. The unmistakable dry aroma of a roasting turkey and the sweet, round scent of baking pies filled the house.

Then, as we sat down for our feast, I saw it. My kid sister had done what our mother did for us, which was to serve cranberry jelly, straight out of the can. So straight-out-the-can that I could still see the can’s seams and lining reflected in the red, quivering blob. I’ve celebrated Thanksgiving at other people’s houses where they served tasty, complicated cranberry relishes with grated fresh ginger, orange zest, and horseradish. But this? This was going to be a meal straight out of my childhood. And it was.

Afterwards, I got to wondering why the cranberry jelly had so much meaning for me. I thought of my Korean immigrant mother, who had been in this country for only five years before I was born. She didn’t have anyone to teach her how to roast a turkey for this most American of holidays. She roasted the turkey as best as she could. Somewhere along the line she learned that you had to serve cranberries and so she did, straight out the can.

The most meaningful foods in our lives are not the advertised ones, not the artisanal breads made with obscure grains or the $6,000/lb. Alba truffles. While these foods are delicious, the most meaningful foods are the ones that wander into our memories unannounced, but lodge there like stray cats that show up at our door one day and never leave.

They’re like bratwurst, an ordinary thing many born-and-bred Wisconsinites don’t learn to appreciate until they move to Los Angeles or Atlanta, or like grilled cheese sandwiches and steaming bowls of tomato soup that speak to us in the wintertime with contrasting tastes, textures, and economic simplicity. They’re the foods that comforted us as children, when we’d had a bad day at school and needed a kiss on the forehead from a loving adult.

The most meaningful foods speak to who we are, where we come from, and the ingenuity of our ancestors. Sausages like bratwurst were the logical outcome of efficient butchery, where an unnamed genius used intestines to house salted animal scraps, organs, and blood, and created a preserved source of protein. Soul food staples like braised collard greens came from a time when African-American slaves had to feed themselves with easy-to-grow vegetables and pig parts no one else wanted.

That same culinary ingenuity is alive and well in Milwaukee. Customers at our Fondy Farmers Market have come up with ingenious ways to preserve the short Wisconsin growing season by blanching and freezing their vegetables en masse. Venice Williams of Alice’s Garden leads “batch cooking” workshops each summer to teach people how to prepare soul food dishes on tight budgets and busy family schedules.

I’ve been pushing healthy eating in inner city Milwaukee for the past 10 years and I’ve come to the conclusion that soul food has gotten a bum rap in our national obsession over obesity. Soul food of the 19th century was a combination of healthy and unhealthy ingredients that kept each other in check until the industrial food system came along and supersized the unhealthy things. Fried chicken was not everyday fare mainly because it took too much time to kill, pluck, and gut a chicken. But now, thanks to the fast food industry it’s possible to feed fried chicken with biscuits, cole slaw, and mashed potatoes to a family of five for under $20.

If we are to move the needle on healthy eating in Milwaukee’s inner city, it will be through inspiring and empowering people to connect with their past through meaningful, familiar foods. The path to healthier diets will not be through cooking education efforts that shame people into eating unfamiliar things and implying that their grandmother’s ways are killing them. As any parent of a toddler will tell you, coercion around something as personal as food rarely works in the long run.

And before we start pointing fingers at the inner city, the latest Milwaukee health data shows that obesity isn’t confined to the poorer neighborhoods. Suburbanites need to watch what they eat as well. As the cartoonist Walt Kelly observed: “We have met the enemy, and he is us.”

So I ask this question of you: What foods bring you the most comfort? What dishes say “family”? Is it healthy? Is it unhealthy? What would grandma or grandpa say about it? What does it say about you?