Ties that Bind

Food Traditions of the Italian Diaspora

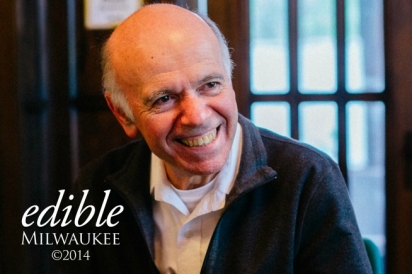

In 1997, Silvana Bastianutti Kukuljan, a retired Milwaukee Public Schools teacher, volunteered to teach Italian to a group of students in conjunction with the Osher Lifelong Learning Institute at UW-Milwaukee.

At the time, she had no idea that the group would endure for over seven years, nor that its members would eventually seek to capture their diverse food and culinary traditions in a self-published cookbook entitled Tastes of Italy (2012).

“We come from many different places,” says Kukuljan. “Some of us are from Italy—or our families lived there—and some of us have traveled extensively to places in Italy. But, food is the one thing that unites and binds us.”

Bastianutti Kukuljan’s own family fled to the U.S. in the aftermath of World War II when their homeland, in the northeast portion of Italy, was given over to Yugoslavia. She was just 16 when her family arrived in New Orleans on a military transport ship and eventually made their way to Milwaukee, where they were adopted by St. Rita’s Parish on the east side.

“It was a sad time,” she recalls. “We didn’t know anyone and had no other family or friends. It was difficult to bond with the Italian population who was already here. Most were Sicilian and had come before the war. They spoke a different dialect and our values were very different.”

So the family looked to long-held traditions, many of which were centered on religion and food, to provide comfort and stability. They observed the annual “Feast of the Seven Fishes” on Christmas Eve, supplementing whatever seafood they could find with polenta and curly cabbage. And they sought comfort in the familiarity of holiday pastries like Presnitz, which was filled with nuts, candied orange peel, and grappa.

Kukuljan’s experience isn’t unlike that of her students, many of whom also had families who left their homelands for U.S. shores.

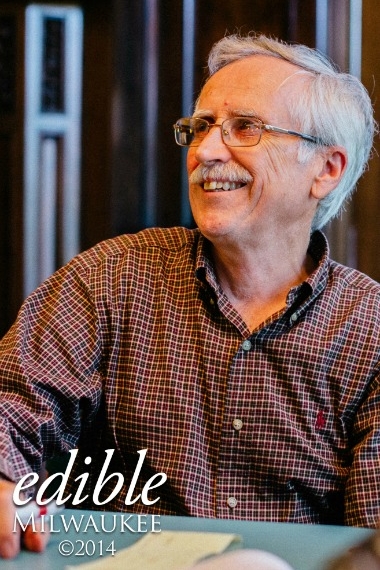

Riccardo Sorbello’s parents emigrated to the U.S. from Toarmina, Sicily in 1920. They settled first in the lower east side of New York, eventually moving and settling more permanently in Brooklyn.

The holidays at the Sorbello’s meant long simmering ragu, spicy sausages, and plenty of homemade wine. But, the annual toast between his grandmother and her brother at the beginning of each meal, was always a particularly memorable occasion.

“Before the start of the meal, one of them would stand-up at the table, raise a wineglass, and recite in Sicilian a simple four-line extemporaneous rhymed poem praising life, love, and wishing for good health,” he recalls. “After that, the other one would stand-up and match (or try to out-do) the previous toast with a different toast. This went on for several rounds, with all of us who were sitting at the table oohing-and-ahhing, laughing, and applauding after each toast.”

Gustavo Ricca’s father was born in 1908 on a family farm in Iron Belt, WI. His family, who emigrated to the U.S. from Ivrea in the Piedmonte region of Italy, settled in the area along with a diverse group of Italian immigrants.

For Ricca’s family, holiday fare included a rotating menu of rustic fare including gnocchi and antipasto, a red sauce made mainly with vegetables, similar to caponata. But one memorable meal for which Ricca still has a fondness is roasted rabbit, served alongside creamy polenta.

The rabbits, which Ricca’s family raised on the farm, were roasted by his grandmother in a wood-burning cookstove.

“She always put some tomatoes with them,” he says. “And the polenta was simmered for at least a half hour. We sometimes served it with gravy, but more often with butter and Parmesan cheese.”

To this day, the dish evokes fond memories for Ricca, who makes occasional trips back to Italy to visit family and explore the food and culture.

“I love it,” says Ricca. “It was on the menu in Torino and I ordered it and I was not disappointed.”

In addition to providing a source of cultural identity, traditions can be a means by which families create connections between the current generation and the ones who came before. Such is the case for Sandragina Ebben.

Ebben’s mother’s family came from Trentino Alto Adige, an area in northern Italy which borders Austria and Switzerland, and was originally part of Austria.

Like many other families, Ebben’s brought a number of their traditions with them to the states. But, one particularly beloved dessert–Fregolotti, a large almond cookie, which is broken into pieces before eating–was lost.

“Because my mother’s mom died when she was so young, my mother hadn’t yet really taken an interest or learned how to cook or bake. But she remembered these things that my grandmother made, including Fregolotti. My mother frequently tried new recipes. But, none of them lived up to the memories that she had of her mother’s Fregolotti.”

However, a trip to Italy in 1997 brought inspiration.

“I had been to Italy a number of times, but my mother had never been back,” says Ebben, “So, after my father died, I took her to the house where her mother and grandmother had been born and lived.”

The experience of returning to Italy rekindled her memories, and shortly after she found a recipe that she declared to be worthy of her mother’s memory.

“It’s buttery and crisp and full of the flavor of almonds,” she says. “And my family now makes it during the holiday season.”

Even better, the tradition now has the potential to be passed along. According to Ebben, at least one of her nieces has taken an interest in the traditional cookie and is learning to make it the way her great-grandmother did.

Copies of Tastes of Italy are available for $18 each. For more information, contact Silvana Bastianutti Kukuljan at silvanabkz@gmail.com.