Chewing The Fat

Rendering and reusing animal fats for future feasts

Two duck legs slowly poached in their own fat sit in my refrigerator, waiting to be seared and savored. Instead of discarding the duck fat, I used it again to confit more legs, and every time I do, I can’t wait to bite into that tender meat. Reusing fats give me a sense of pride—I’m being economical and resourceful, using what I have rather than running out to buy more. Rendering animal fat takes work, but with patience you can do it yourself.

Historically, cooking with animal fats was the rule and not the exception. Lard was the cooking fat of choice in American and European households up until the early 20th century, when it was edged out by vegetable shortening. Home cooks saved bacon fat in jars. Leaf lard from around a hog’s kidneys made perfect pie dough. Whereas Gentiles cooked with lard, Kosher Jews used schmaltz: rendered chicken, duck, or goose fat. Schmaltz is made by slowly cooking bits of chicken skin, adding chopped onions after the skin turns golden brown. The cracklings and fried onions are called gribenes. Sautéing vegetables in schmaltz or any other animal fat adds an additional layer of flavor. For example, homemade popcorn with duck fat tastes rich and earthy compared to the neutral taste of vegetable oil.

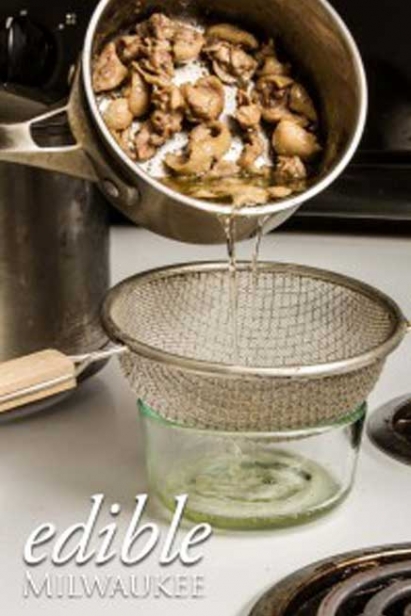

Duck is on the menu where I work as a line cook, so I render duck skin quite often, by simmering small pieces of skin in a pot at a low temperature, which eventually allows the fat to melt out. To kickstart the process, I add a small amount of water, enough to cover the bottom of the pot. The water evaporates as the fat melts and becomes clear. I stir the pieces occasionally so they render evenly. Be sure not to brown the skin too much—the melted fat will taste “cooked,” like fryer oil (see the sidebar on how to dispose used vegetable oils). When strained, duck fat can be kept in the refrigerator for six months or stored indefinitely in the freezer, as long as it’s in an airtight container.* This method also works for schmaltz. If you’d like tallow, you can slowly cook small pieces of suet (raw beef or mutton fat). The same process applies to lard. You can ask your local butcher or farmer if they sell suet or fatback.

Duck, Duck, Goose

Groceries and butcher shops don’t sell poultry skin by itself, and rendered fat can cost as much as $12 per pound. Tower Chicken Farm, 4111 S. 6th St., a Milwaukee butcher shop devoted to all things beaked-with-wings, has the lowest price in the immediate area for duck fat at $7.75** per pound. To get the most for your dollar, try rendering duck fat yourself (the same process works for chicken and goose). You’ll need to break down a whole duck, which will cost between $2.99 to $4.99 per pound. A whole bird leads to more than one meal: the skin can be rendered and the fat used like vegetable oil, the breasts can be pan-fried, the legs braised, and the bones can be used for stock.

After butchering a whole duck and taking off excess skin, I rendered one pound of duck skin for 90 minutes until the fat turned clear. The yield was about 3/4 to 1 cup of melted fat. I bought the duck from Pacific Produce, a local Asian grocery store, for $2.99 per pound. I could’ve bought already rendered fat from Tower Chicken for $7.75 per pound. But I saved $4.76 per pound because I wanted to render fat myself. Granted, I broke down three ducks to get three cups of fat. But with all that meat, I marinated duck breasts in white wine and cooked them for lunch and dinner. I roasted bones and made a rich stock.

Utilizing every part of the animal takes time. But for me, I don’t mind the work. It’s about applying what I’ve learned as a line cook and doing it at home. When I first learned how to break down chickens and ducks into breasts and legs, I was scared to make the first cut, afraid that I would screw up. But no one gets it perfect the first time, or even the second and third. Butchering takes practice. Rendering your own fat requires long-term thinking. Even when you’re standing over a pot of simmering duck skins and thinking ‘Am I doing this right?” keep going. You learn from mistakes. And, when you get it right, eating duck legs you poached in fat you rendered yourself is even more fulfilling.

OIL ALL USED UP? HERE’S WHAT TO DO WITH IT

The City of Milwaukee collects used cooking oils that are later refined into biodiesel fuel. City residents can drop off used vegetable oils at Self-Help Centers, which are located at 6660 N. Industrial Rd. and 3879 W. Lincoln Ave. (Call 414-286-CITY for days and hours of operation.) In 2014, the city collected 3,140 gallons, said Sandy Rusch Walton, spokeswoman for the city Department of Public Works. Since fall 2011, when the effort began, the city has recycled about 10,400 gallons.

Walton said recycling oils benefits the city by keeping them out of the sewer systems where grease can lead to clogs, basement backups, sewer overflows and expensive plumbing repair bills. Waste is turned into a cleaner burning fuel, which is better for the environment, she added. The city works with Blue Honey Bio-fuels, of Ettrick, Wis., to collect and refine used cooking oils.

Residents can only drop off used vegetable oils, such as canola, soybean, palm, sunflower, corn, and olive oils. Butter, lard, and other animal fats are not permitted. The City of Waukesha also accepts used cooking oils from all Waukesha County residents at the recycling drop-off site at 750 Sentry Dr.