Milwaukee on the Rocks: A Curious History & Intriguing Future of Ice

A couple of years ago, I moderated a panel discussion about how Milwaukee was being shaped by insiders and by outsiders. One of the outsiders - the people from away - on that panel was Heather Terhune, who had recently taken over as the executive chef at Milwaukee’s Kimpton Journeyman Hotel and its dining spots - Tre Rivali and, well, The Outsider.

She said a lot of things on that panel - everyone did. But one tiny detail stuck with me for weeks afterwards. “I buy ice,” she said, “from Chicago.” It was a detail that stayed frozen in my consciousness because a) it sounded vaguely mad; and b) I had heard that Milwaukee once had a robust - a veritable champion - ice industry. So how had the city responsible for generations of cold beer slid so far down the slippery slope that establishments here would turn to Chicago to chill their drinks? And is there anyone who might step in and restore Milwaukee to its frosty place at the top of the glacier?

It would take a couple of years, and countless tortured metaphors and bad ice puns to find the answers.

Milwaukee and Ice: The Early Years

Thirty-one thousand years ago, ice was a really big deal here. If Heather Terhune had lived in Milwaukee in those days, there would have been no need for her to call down to Chicago for more ice because she could have stepped out of her house and satisfied all of her restaurants’ ice needs forever. In fact, her house’s door would have been frozen shut by ice in the form of a glacier called the Laurentide Ice Sheet, which buried much of Wisconsin for 10,000 years. But while the glaciers left behind many of the distinctive landforms that literally shape southeastern Wisconsin today, they did not leave ice cubes behind, and so the humans who settled the region much later had to result to creative ways of finding ice and putting it to work for them.

The 19th and Early 20th Century: Like Ice Fishing… for Ice

In 2018 Wisconsin, when you see people and structures on a frozen lake, you can be pretty sure of two things – that there’s a nearby hole in the ice, and that beer is involved. One hundred fifty years ago, that was also the case in the region, but the people and the structures weren’t there to catch fish, they were there to catch ice. Or to harvest it, at any rate. Despite the Ice Age’s demise, Wisconsin’s climate was perfect for the natural development of an ice industry. And the ice industry made it possible for Milwaukee’s beer industry to boom.

“Wisconsin’s lakes themselves were often an ice-cutter’s delight,” wrote Lee E. Lawrence in “The Wisconsin Ice Trade,” heretofore the definitive history of the ice industry in the state. His article appeared in the Summer 1965 issue of The Wisconsin Magazine of History, about a year after he gave a lecture on the same topic to the Economic Historians of Wisconsin that is, sadly, not available on YouTube. And “the primary reason for the rise of a large-scale harvesting and shipping of ice was the expansion of the brewing and [meat]packing industries in Milwaukee and Chicago.”

Historian John Gurda backs up this story. “It’s hard to believe today, but in the early years – all the way back to the 1840s – brewing was largely seasonal,” Gurda explains. “You would brew in the colder months and sell in the warmer months. And what kept your brew drinkable during the warmer months was ice. You didn’t have refrigerators.”

That was especially an issue as tastes changed in the late 19th Century. “The development of a large beer-drinking public,” Lawrence wrote (referring, we assume, to numbers of beer drinkers and not their relative girth), “and the transfer of popular preference from heavier and more alcoholic malt liquors to lighter and more effervescent beers, at once helped to make Milwaukee famous and created an important demand for ice.”

In the late 19th and early 20th Century, rivers and inland lakes such as Pewaukee Lake were lined with a phalanx of ice houses that harvested, cut, and stored ice. “They’re long gone,” Gurda says, “but they were kind of the equivalent of skyscrapers in Waukesha County in those days. They really dominated the skyline.”

Gurda says the ice harvest bore a significant resemblance to that of crops grown nearby, in warmer months. “It was almost like plowing a field,” he explains. “These were horses that had studded horseshoes, so they wouldn’t slip, and it would have an ‘ice plow,’ that would scribe a line, so the drivers had to keep them very straight.

“So [they would] begin with a straight line, and then they had kind of an outrigger that would draw a line for the next furrow. By the time they were done, you had kind of this grid of shallow furrows in the ice.”

After the blocks of ice were cut from the water, day laborers would use pike poles to drag the blocks to shore, where they were winched onto conveyor belts, and brought into the sawdust-lined icehouses for storage. Storing ice allowed breweries and large meatpacking companies like Patrick Cudahy and Armour to sell fresh products well after they were produced – and to ship them via rail to customers around the country.

At the same time, the federal Clean Water Act was still a century away, and so companies had to be – shall we say - circumspect about where they got their ice, even without public health authorities demanding it. “In the harvesting of ice,” Lawrence’s article diplomatically lays out, “some concessions were made to a hygiene apparently based on no more than the feeling than what smelled intolerably in liquid form should not when frozen be added to drinks or brought into close contact with food in storage.” By the 1880s, companies working the Milwaukee River would generally cut ice only above the North Avenue Dam.

Meanwhile, Lawrence says, icehouse workers had developed a reputation for carousing and brawling when they weren’t cutting apart the surface of lakes and rivers.

At the height of Milwaukee’s ice production days, hundreds of thousands of pounds of ice were harvested from the area’s lakes and rivers. But by the early 1920s, most of the commercial ice harvest had disappeared, made obsolete by the advent of mechanical refrigeration. Eighty years later, civic leaders would talk about making the city a “world water hub.” Historian John Gurda says it was fair to call this period “a time when Milwaukee was a world ice hub.”

Gurda, for his part, may soon usurp Lee E. Lawrence as the voice of authority on ice in the region. His 21st book, due out this summer, is called Milwaukee: A City Built on Water, and includes a full chapter on the ice trade here.

Wisconsin in the 21st Century: The Return of an Ice Harvest, Of Sorts

So that brings us forward to the 21st Century, the drinks Heather Terhune helps craft at Milwaukee’s Kimpton Journeyman, and her specific demands for ice cubes to cool those drinks. As you undoubtedly remember, she buys them from Chicago, but it not so much their origin that’s important as it is their shape and size.

“I am a self-proclaimed ice snob,” Terhune proclaims. That snobbery came as a result of five years at Sable Kitchen and Bar in Chicago, where customers called for drinks that were not only cool in temperature, but cool to look at, as well. “That’s where I really came to learn about dilution of ice and how important it is.”

If you read that last line and felt the slightest degree of skepticism, Terhune says she knows where you’re coming from. “I’ll be honest,” she concedes, “when I first started, bartenders started talking to me about it, and I was, like, ‘That is ridiculous – it’s the most absurd thing, and it doesn’t make any sense.’ And then, I said, ‘Oh – wait. They have a point.’”

So for her drinks Terhune sought out ice that worked from both an aesthetic and a practical standpoint. “It’s crystal clear, perfectly sized, and it really does make a huge difference,” she explains.

She took her exacting standards with her when she relocated to Milwaukee. The Kimpton has, on hand, two different ice machines – one made by a company called Kold-Draft and the other by the Japanese company Hoshizaki. The two machines make high-quality, medium-sized cubes and crushed ice, which cool everything from Tiki drinks to iced coffee. In the case of cold-brewed iced coffee, Terhune says it’s desirable for the ice to melt and dilute the coffee and make it a little less strong.

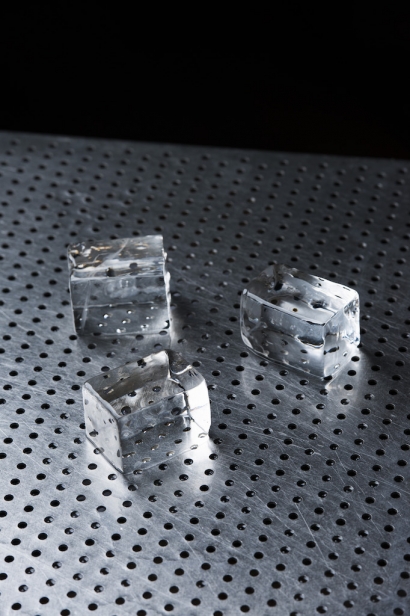

But for whiskey, martinis, or other drinks that are better when they’re full-strength, Terhune calls in the big guns - or the big cubes, anyway. She uses large format ice – cubes that are two inches by two inches, take up a large part of the real estate inside a glass, and don’t melt quickly, meaning that the taste of the drink is consistent from start to finish, unless you drink it really slowly. Hers were the first drinks in Milwaukee to routinely use large format cubes, and it required her to turn to Mike Ryan, a former coworker at Sable, who had started his own craft ice company in Chicago, called Just Ice.

Terhune still gets her ice from south of the border, but as other Milwaukee bars and restaurants have gotten in on the large-format ice trend, a couple of Wisconsin entrepreneurs have started to chip away at the market. Milwaukee-based Joey Houghtaling and Madison-based Mike McDonald are the proprietors of Beaker and Flask, the first large-format ice makers in southern Wisconsin since the days that day laborers winched huge blocks from a frozen Pewaukee Lake.

The company has been operating out of the back of State Line Distillery in Madison (where McDonald’s titles are bar manager and spirits ambassador) since last fall, and the business partners have plans to open another production facility in Milwaukee. They have a growing customer base in both places, including places such as Boone & Crockett in Bay View, and Lucky Joe’s in Wauwatosa. The chill-sounding McDonald says one customer even bought their ice for use in making Sno-Cones.

McDonald says Beaker and Flask makes about 600 pounds of ice each day, which yields between 500 and 600 large-format ice cubes. His company uses reverse-osmosis water and a Clinebell machine, which is essentially a lined, two chamber freezer. “It has two pumps that circulate the water,” McDonald says. “So as the water is freezing from the bottom, the water is circulating continuously. So every moment as the ice is forming, all the impurities rise above [the ice], and they keep rising to the top - to the point where it’s completely frozen, and only a small amount of impurities remain.”

At that point, the process takes on a familiar refrain. McDonald uses an engine-powered winch to lift the large blocks of ice from the Clinebell machine, much the way ice was hoisted from the frozen Milwaukee River, only without the nearby smells or the brawling workers. It’s cut first with a chainsaw, then trimmed further with a table saw before the finer cubes are cut.

It’s a time and labor-intensive process, but the result is a cube that is noticable both for its cost - 50 cents or more per cube - and for its aesthetics. In fact, McDonald says there’s an irony in making a perfect large-format ice cube. “In a drink like the gin old fashioned,” he says, “once the ice is really tempered, it’s almost impossible to even see it.”

But while McDonald’s company may be on the cutting edge of the ice industry as it exists in Wisconsin today, he says he still holds an appreciation for the way it was once done here. “I’ve heard that up north, they’re still pulling ice out of the lakes,” he says. “I’d like to experience that someday - it would be cool.”

Of course, just about everything about ice is cool.