Our German Soldiers

A Place in Milwaukee During Wartime

Walk up the steps to Dom and Phil DeMarini’s Pizza in Bay View and you’ll be walking through the doors of history and into the building where thousands of German prisoners of war slept.

In 1944, as the Allied troops invaded North Africa and began the northward sweep up the boot of Italy, the United States was faced with a new problem: what to do with the captured German troops. As the battle raged, it became apparent that the only solution was to transfer the captured enemy back to the United States. Throughout the country, camps were established to provide secure detention to over 400,000 captured Germans. Wisconsin became a temporary home to 40,000 of these PWs (to use the Army’s preferred acronym). We were considered an ideal location, given our German heritage and stillthriving German language culture. Military intelligence officials were very concerned about localized Bund activity and conducted thorough interviews with all detainees to ensure that only non-political soldiers were sent here.

Their existence was initially considered classified, as the government was anxious about local reaction to having enemy soldiers in the “homeland.” Funnily enough, according to military reports, the Army was not concerned about retaliatory reactions against the German soldiers—they were concerned that local residents would come to camp look for their relatives. This concern turned out to be justified.

Milwaukee became the home of 3,000 Germans captured in the North African campaigns of 1943. The detainees arrived at Camp Billy Mitchell, hastily constructed on what is now the Grange Avenue entrance to Gen. Mitchell Field International Airport, in the winter of 1944, having spent the previous year in south Texas.

Camp Billy Mitchell

At Camp Billy Mitchell, a workshop was constructed to make batteries for the Rayo-Vac Company for radio testing. This work was done, but not without complaint. Written in the propaganda-style of the day, the Milwaukee Journal reported March 18, 1945: “They know the Geneva Convention better than the Horst Wessel Song and inquired about all sorts of delicate points before getting down to business.”

A Milwaukee Police report from February of 1945 details picking up two German PWs on First and Mitchell Streets. The detectives stopped the men thinking they were suspects in a check fraud scheme. The PWs quickly confessed that they walked away from the Camp and were having a great time going to taverns. The Germans were then returned to camp and soon after, guard towers were erected.

As the spring weather came to Wisconsin, and the ban on reporting about the PWs was lifted, the temperament of guards and prisoners relaxed. Through the Red Cross, relatives were notified that kin were nearby. Gertie Haas of Milwaukee told her story to the local history project, Stalag Wisconsin: “Over the several months of Cousin Louis’ stay, Dad received permission to visit. He brought packages that included cigarettes, cookies, candy and fruit. It was always a pleasant visit.”

No Fraternization!

Area businesses whose labor force had been either drafted into the military or requisitioned for war work applied to use PW labor. The greatest need was in area farms and canneries. All armies fight on their stomachs, and bringing in the harvest of 1945 was critical.

Donald Look was the purchasing agent for the Nieman Cannery. (In 1945, it was also affiliated with the Nieman/Fromm silver fox farms.) The cannery worked to preserve the incoming pea harvest, but also processed a variety of vegetables grown in the area.

Mr. Look was in charge of selecting and managing 50 PWs to work at the cannery and farms. Mr. Look says this of the PWs: “Our group were all real gentlemen. None of them had wanted to go to war to kill any other person; they had been forced to fight.” The workers he chose all spoke a little English, but many of the civilian workers also spoke German.

Willi Rixen was a well-regarded artist before being drafted into the Wehrmacht. Often ill with an ulcer, his civilian co-workers shared fresh eggs, milk and fruit as he could not eat much of the food served at the camp. Helmut Tichy was a Viennese Süßwarenhersteller—a very specialized type of confectionary maker. (Not a cake. Not candy. Think Mendel’s in Wes Anderson’s Grand Budapest Hotel.) Hans Giese was a teacher. Konrad Mertel a machinist. Alfred Klutentrater a gifted composer and musician.

Work at these companies was varied. A group of PWs worked at the cannery, processing vegetables. Another group worked caring for the silver foxes. And yet another worked in the slaughterhouse rendering horses into food for the foxes. Mr. Look noted that the Niemans often allowed the PWs working in the slaughterhouse to cut steaks from the horses to take back to the camp. Food for everyone was rationed, with less allocated to PWs.

The camaraderie and friendships formed at the Nieman cannery and fox farms were not unique. Thousands of PWs were sent to temporary camps in Door County that summer to bring in the cherry harvest. Growers publically stated that the entire year’s crop would have been lost without the labor of the German PWs. Further south, in Franksville, PWs brought in the cabbage crop and worked in the sauerkraut factory.

War’s Over. Now What?

The war in Europe was over in May of 1945, but German PWs were still considered just that—Prisoners of War— throughout the summer as the fighting focused on the Pacific theater. As the summer passed, rules relaxed for the PWs at Billy Mitchell.

Many earned the privilege to leave the camp to visit the taverns on South Howell Avenue. No one attempted escape. Where would they go? Europe had been decimated by fighting. Few knew if they had homes to go to, let alone if their families were alive.

As PW workers, they earned 80% of the minimum wage of civilian workers. They were paid in camp script, which could be used to purchase necessities from the camp store. They could also save their pay in a government-sponsored savings account. So they worked and waited.

The Harvest Party

The prisoners of Camp Billy Mitchell grew close to their civilian co-workers from the various farms and factories in Southeastern Wisconsin. The PWs wanted to thank them for their kindness and generosity by hosting a Thanksgiving banquet. Here is Donald Look’s memory of the evening:

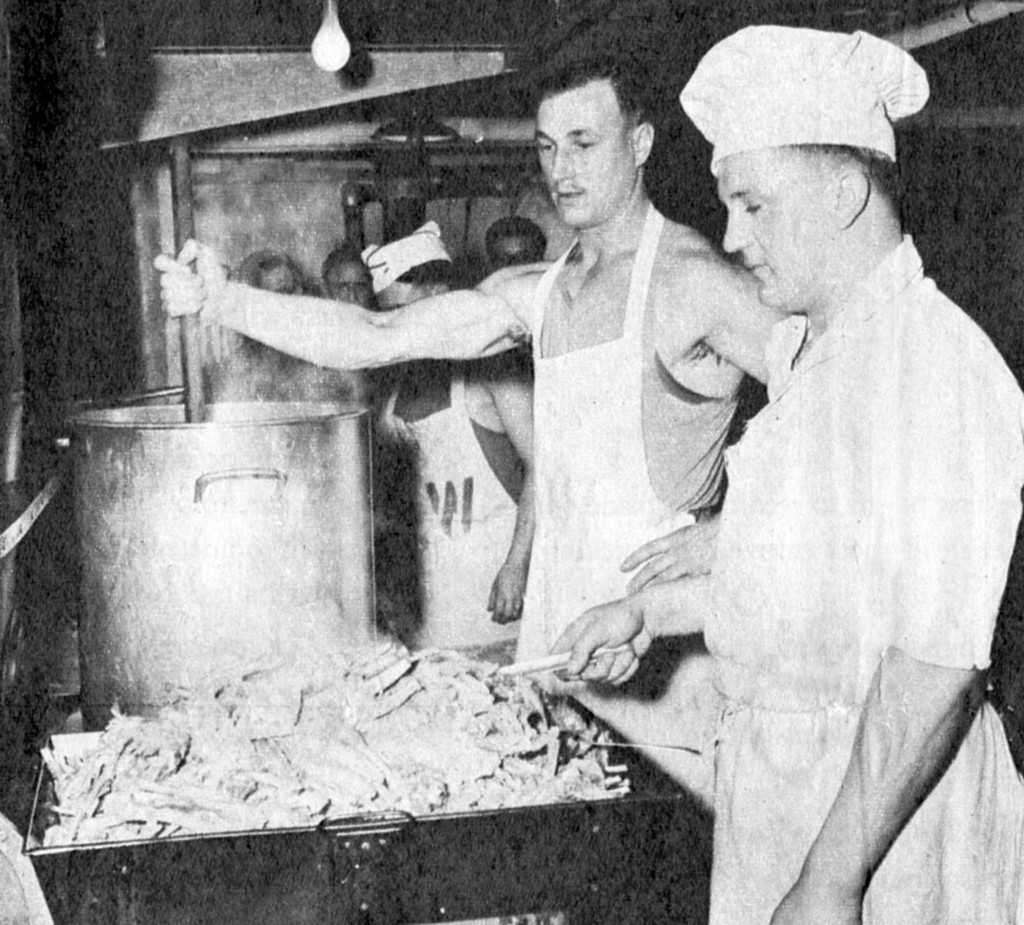

“On an evening in late November, after the season’s work was done, a group of the employers of the POWs were invited to a banquet at Camp Billy Mitchell, prepared and served by the men who had worked for us. It was a great assortment of the finest foods we had ever eaten. And I had a chance to enjoy Helmut Tichy’s confectionary, and it was all and more than he had bragged about. During the dinner, the 11-piece German Concert Orchestra led by Alfred Kluentrater played German songs, Christmas Carols and parts of the Mosel Wine Song.”

Diligent research has not uncovered the rest of the menu for the party, but many personal stories note the skill of the PW cooks. Former guard Robert Heldt said, “We ate in the same mess hall as the PWs. They got organ meats and we got better cuts. I remember boxes and boxes of frozen livers were trucked in.” An unnamed former PW recounted to an interviewer, “When I was captured, I weighed 125 pounds. When I came home, I weighed 185 pounds! We ate good in Wisconsin.”

The German PWs left Camp Billy Mitchell in early December of 1945. Most were sent to France to be eventually repatriated. The PWs, who worked for Nieman Cannery, sent letters to Donald Look that they were treated poorly by the French and were working in mines. Mr. Look sent many letters and packages, but none made it to the intended PWs.

The Closing of Camp Billy Mitchell

As the PWs were sent back to Europe, the camp was officially closed in May 1946. Jobs and housing became the focus of civic leaders. The camp barracks were dismantled and repurposed as American Legion and American Veteran Posts. One stands in Greendale and is still used as a Post location. The other is in the Bay View neighborhood and is, of course, the home of Dom & Phil DeMarini’s Pizza.

Peace

Bringing German prisoners of war to the American heartland helped the United States government achieve something that no amount of propaganda could do: make a lasting peace with Germany.

Governments have ideologies and political ambitions, but people all over the world want the same things: to live in safety and provide for their families. When an enemy is made human, our own humanity grows. As Donald Look said to end his notes, “We tried to treat the POWs in the way we hoped our enemies would treat American POWs wherever they were.”

Photograph courtesy of the Milwaukee County Historical Society

Special thanks to Steve Schaffer, Assistant Archivist, Milwaukee County Historical Society for his assistance in locating the Donald Look documents.