Blue Horizon: Water & Milwaukee's Future

“Where there is water, the is Anishinaabe.” This statement, passed down generation to generation by the Ojibwe, who were the first residents of Milwaukee. A city whose name, ominowakiing, meaning “Gathering place by the water”. One of branches of the Anishinaabe, or first nations, the Ojibwe migrated from the North following their prophets instructions to “go to where the food grows on the water”, finding sustenance in their dietary staple, wild rice, which grew in the river valley that now goes by their name for it, Menomonee. A deep interwovenness of water, informs Milwaukee’s history, evolution and identity, from it’s earliest residents. Home to a soil rich geography, which is trisected by 3 rivers, all pouring out to one of largest cachees of fresh water on the planet, Milwaukee was made by water.

The 5 lakes which together form the Great Lakes Basin, though millions of years old, have in the last decade been the the focus of more innovation, thought and policy than ever in their history. The Great Lakes Basin, of which Lake Michigan is a part of, encompasses 33 million people, and geolocally and aquatically links the Montreal Canada, with Duluth Minnesota and Gary Indiana. Locally, as Milwaukee’s river marches, once thick with wild rice and game, gave way to the primacy of fertile farming soil, a river a system and versatile deep water port that provided accessibility and economic opportunity, goods were grown and shipped out to the markets of the world. Milwaukee owes its very existence to the waters that flow among its streets and washes upon its shores.

Wisconsin’s well known and storied history with agriculture goes back early 1800’s. What many may not know is that agriculture accounts for 80% water consumption in the US, and Wisconsin is the the nation’s number 2 largest national provider of milk, 1st in cranberries and ginseng, and 4th in meat and poultry production. As a farm-centric state, water is a fundamental and vital resource. From grains to forage crops for pork and cattle, potatoes and cherries, carrots and peas, all of which are high value food stuffs grown in Wisconsin, water, and access to it, is everything to our 88 billion dollar agricultural industry. Without our water, we have less food and drink to grow, make, and export, which we do, to over 145 countries, returning well over 3 billion dollars back to the state.

As humankind moves ever deeper into the 21st Century, communities situated on or near the earth’s great catches of fresh water, be they lake or riveways, hold a distinctive and privileged place though their access to what is readily becoming an invaluable resource to individual citizens and corporations alike. In his prescient understanding of water and its role in prosperity and geopolitical issues, President John F Kennedy once stated, “Anyone who can solve the problems of water will be worthy of two Nobel prizes-one for peace, and one for science.” Owing that with every privilege comes a responsibility, Milwaukee has been leading the regional and global charge for water stewardship and sustainability, technologies and education for decades.. Water, is a 10.5 billion dollar industry for the MIlwaukee area. Though only snapshots of the constellation of dynamic entities and personalities, thinking “water” in Milwaukee, these are some of the stories that hearld our connections to water.

Lucy Saunders never meant to start a regional conference on water. As one of the original organizers of The Great Lakes Water Conservation Conference, she was really just interested in beer. A Milwaukee based brewing guru and the author of 5 books on beer and cooking with it, she had been keen to the vitality of water in the brewing for a long time. Most beers, save for porters and the like are 96% water. ” “Water is a heavy ingredient.” she says with a knowing glint in her eye, enjoying the double entendre. It’s necessity in so much of what we consume or make is paramount. Additionally in brewing, is it vital, and requires significant amounts of energy in the brewing, heating, cooling and just moving around. It was as an attendee to a Michigan Brewer’s conference years prior to the The Great Lakes Water Compact, which signed into law by the governors of the 8 states associated with the Great Lakes Basin in 2007 and 2008 respectively, that Saunders had a realisation:” I looked at the schedule for the conference and water wasn’t even a topic.” she said. Committed to change that, she and 10 volunteers, which ultimately grew to hundreds have hosted 7 conferences in and around the Great Lakes Basin. Gathering in Milwaukee, Rochester New York and St. Louis among basin cities, the conference brings together craft brewers and water academics to cross pollinate over ideas and practices regarding the responsible use and the sustainability of Great Lakes water. A vehement and exceptionally well-connected activist on issues of great lakes water and it’s future, it’s notable that all her work in water is as volunteer. “The first time I saw Lake Michigan I just fell in love” she told me. “It’s that line of blue on the horizon, there is nothing like it.”

The North American Alliance for Water Stewardship covers a lot of territory from it’s office in Milwaukee. All of North America. It’s members, which number over 100, are some of the largest corporations in the world; Nestle, Coca-Cola, General Mills, Millercoors, and all have one thing in common. Their heavy reliance on water. The AWS works to establish a standard for how large water users optimize water to ensure their footprint doesn’t impact their respective watersheds. Matt Howard, the Director for the AWS, who previously headed Milwaukee's Office of Sustainability for five years before joining the Alliance in 2015 sees nothing but opportunity for the Alliance and speaks warmly of how Milwaukie is uniquely situated in this global dialogue around water. “You would be surprised,” he said, “ at how many companies are heavily water dependant that consider water an afterthought. We have 200 plus water tech companies right here.” He stressed, “ we are huge in water industry and research. That speaks volumes to company leaders when I meet with them. The standard the AWS implements for the member companies” is similar to a LEED Certification.” he says.

LEED, Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design, is a rating system to evaluate the environmental performance of a building and encourage market transformation towards sustainable design. From the AWS office in Milwaukee, Howard to brings that standard to heavy water use companies of North America. “(Water)It’s really our most valuable resource” he says.

As an undergraduate at Marquette studying civil engineering, Paige Peters had no idea people would one day call her a radical. Returning for graduate work, she and her professor Dan Zitomer worked on problems with wastewater common to over 700 American cities: combined sewer and rainwater pipes. A non- issue, until, heavy rains fall and fill the pipes before the sewage can be processed, a city has only two options: flush the pipes combined with sewage and rainwater out into the environment, (for Milwaukee this is Lake Michigan) or have backups into residents basements. Over the course of her Masters Degree Peters and Zitomer developed a high rate wastewater treatment system. Narrowing the 8 hour treatment time frame the Milwaukee Jones Island Treatment Plant would take, to 30 minutes, Rapid Radicals, the company, was born. “The idea is to have a modular system” Peters says.“for rapid treatment that could be retrofitted to existing treatment plants, or at locations prone to seeing overflows, or even transported on the back of a truck, for disaster relief scenarios” Much of the research and development was funded by the National Science foundation. “We are doing really promising things with water in in Milwaukee.” Peters’ said.

In 2007, Rocky Marcoux, Commissioner for the Department of Development for the City of Milwaukee, declared that Milwaukee was indeed, “the urban agriculture center of the country”. Sweet Water Organics, and the Sweet Water Foundation, would echo that statement when founded two years later in 2009. Created to further hydroponics, or the system in which plants are grown indoors and derive their nutrients from water, sand or gravel, instead of soil, it is a hallmark of urban agriculture. Two entrepreneurs, Josh Fraundorf and Steve Lindner, toured Growing Power with Will Allen and seen a small version of hydroponics, and were bent on scaling it up, after being struck with the business viability and ecological benefits. The system, in which fish are raised in tanks near the plants, with a circular water flow to both, produces two profitable food sources, fish and edible greens. The fish waste provides nutrients for the plants which are grown in the now nutrient rich water. The water is kept clean for the fish by the plants roots. Jim Godsill, who is the president of the board of The Sweet Water Foundation, which seeks to scale out hydroponics concepts and practices to schools and learning centers globally, was the connecting personality. Ultimately Sweet Water Organics would repurpose a former industrial space in Bayview, with fish runs and plant beds to a scale that caught the attention of national and international press and researchers. Three 10,000 gallon tanks holding fish and growing plants above would absorb much of the former factory space. Press, like the The New York Times to the Travel Channel beat a path to Sweet Water’s door. Ultimately the great recession of 2008 would undermine the early financial support of Sweet Water Organics, but the Sweet Water Foundation would abide. None the less the legacy of Sweet Water Organics scale and reach lives on. The commissioner was right.

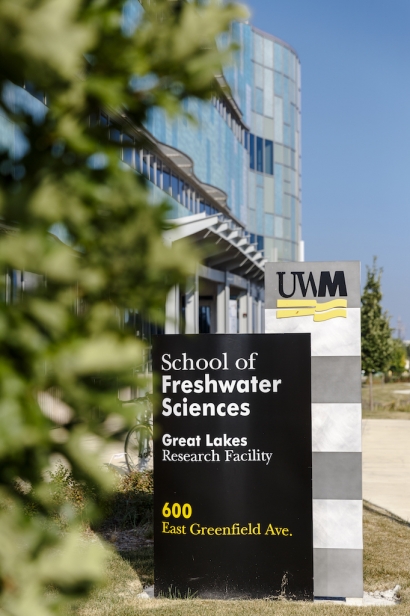

When you think of Hollywood you think of movies, Silicon Valley, tech, Nashville, country music. When you think of Milwaukee in the near future, the world is going to think water” says Rich Meesun, the co-chair and co-founder of the Milwaukee Water Council, as well as the CEO of Badger Meter. “The ah ha moment came when I was touring AO Smith’s flow labs, which are very similar to ours and just about 4 miles down the road from Badger Meter, and I thought there are hundreds of companies working on water in SE Wisconsin, we have a real center here! ” After a discussions with Julia Taylor at the Greater Milwaukee Committee, and dozens and dozens of calls to other CEOs of companies aligned with what Meesum calls “wet industry” the Water Council was born in 2009. Much of Milwaukee’s industrial 19th and 20th century might came from water intensive industries, such as brewing and tanning. “Many of those industries are gone from Milwaukee, but the little companies that sprung up to support them with valves, meters and ways to move water based products are still here” he points out. “We have the biggest density of water industry, tech and education in the world’ Messum notes enthusiastically. “The only others that come close are the Netherlands, Israel and Singapore..and by the way, those are countries, we are just a region inside of state.” he says with a deep note of pride in his voice. The water council, since its inception has become a locus for advancements in water education, talent development, technology, and an economic driver. Meesun points to the relocation of Zurn world headquarters from Erie Pennsylvania to Milwaukee, just to be a part of the constellation of water centric work in Milwaukee. We have the only School of Freshwater Sciences in the world through UW-Milwaukee” he said, “UW-Whitewater is the only school on the globe that offers a degree in Water Business. Marquette, MSOE the list goes on, plus all the industries working together.” When asked about the next decade of accomplishments of the Milwaukee Water Council, Meesun smiles, “We are already 10 years ahead of where I thought we would be when we began to conceive of the council” he says. Water, and how we create jobs, ensure sustainability, even work to solve the world’s problems has moved from an “interest” to a “theme” for Milwaukee, thats the amazing foundation we have here” he says.

Milwaukee’s rich tapestry of water research, industry and innovation is not hard to miss. The region is a locus for water education and research, and employs a tremendous amount of people in water centric industry, and sustainability. Through our “thinking water” Milwaukee is changing the course of its use worldwide. There are other places on the globe, where water is more scarce. Others were its value more readily directs policy and politics, but few that have thrown their fate in so consciously and actively behind water and it’s future for both our region, and the greater globe. Milwaukee came into being because of water, and it seems it will endure, and remain an asset to wider world because of it as well.