When Students Become Teachers

Food mentors share wisdom, their charges pass it on

“No one is born a great cook, one learns by doing.”

This axiom from Julia Child is one that chefs and other food artisans have surely heard more than once.

Learning by doing is significantly easier, however, when hard-earned knowledge is passed down over stoves, tables or vats by someone who has been there before. Almost every role in the food business has a predecessor.

The building of relationships between food mentors and their charges is critical to mutual success.

Perhaps most surprising is the depth and breadth of the impact these food mentors have had locally on the people, places and communities they’ve touched.

Different paths, same destination

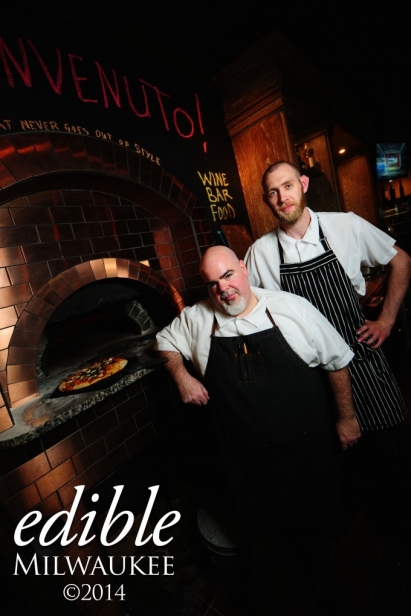

During a recent grand re-opening party for friends and family, a peek inside the newly remodeled and re-imagined Mangia Wine Bar in Kenosha revealed this dynamic. As guests heartily greeted one another, drank wine and sampled items from the new menu, the new energy brought out by owner Tony Mantuano and Chef Jason Gorman hummed.

Mantuano, a Kenosha native and James Beard Award-winning chef, opened Mangia in 1988 with brother Gino and father Gene. This year, he and wife Cathy remade the former trattoria into a more casual, vibrant place featuring new dishes and an increased emphasis on wine.

Gorman, who worked for other well-known chefs in Atlanta and Dallas, got to know Mantuano during his seven years as executive chef at Dream Dance at Potawatomi Bingo Casino. Following Gorman’s stints at the Iron Horse Hotel and La Merenda, a mutual respect led Mantuano to hire him to breathe new life into the restaurants at the Art Institute of Chicago.

Gorman said that after embracing the challenge of overseeing multiple restaurants and large events, he yearned to have more direct interaction with the food and guests than his role there usually afforded him. Plus, he wanted to get back to Wisconsin and his Italian roots.

“Jason wanted to continue our work together, but to get back to a single kitchen environment where he could work on the line and get his hands dirty,” said Mantuano. “So he offered to come to Kenosha. I said, ‘are you sure?’ It’s a little challenging to get people to move to Kenosha. But he wanted it, and it’s been great for both of us.”

“Working with Tony in different environments really helped my cooking at Mangia, because I developed an understanding of how he wanted things done,” said Gorman. “The attention to quality, freshness, the simplicity of the ingredients. It’s a philosophy we share, and he gives me a lot of latitude to execute that. It’s comfortable.”

As someone who spent the early years of his career in Italy learning the craft of cooking alongside some of the legends of Italian cuisine, Mantuano understands the value of a mentor’s guidance.

He recalled how chef Nadia Santini at Dal Pescatore taught him to cook pasta half way, then add it the tomato sauce to finish cooking so the pasta absorbed the sauce, and the flavors married.

“It was a revelation,” he said, one of many that stuck. “We still have a dish on the menu at Mangia called Spaghetti Alla Nadia after her.”

The lessons Gorman learned from Mantuano and other chefs he’s worked with are regularly passed on to his sous chef at Mangia, Taylor Bogardus.

“Taylor’s very passionate and driven, and I’ve seen how he interacts with and tries to motivate the team,” Gorman said. “He gets people excited about what we’re doing by doing it alongside them instead of telling them what to do. Managing people is the hardest part of this business, and he’s a natural.”

Mantuano affirmed Gorman and Bogardus are a formidable pair. “Ours is a really small kitchen and those two guys are working right next to one another,” he said. “When you’re in the trenches like that, you need to count on your brother-in-arms to hold up his end.”

Gorman advises young chefs to have a goal in mind, make sure they’re doing what they love, and that attitude is always more important than technical skill.

“I can teach you how to cook a steak, but I can’t teach you how to care,” he said. “Being a chef isn’t what you see on TV. It’s long, hard hours, time away from family. You’d better love it, because it’s not a sprint, it’s a marathon. I always tell my cooks, ‘we’re not doctors or firemen or policemen, we’re not saving lives, but for 90 minutes, we can make people happy with great food.’ That’s enough for me.”

Up through the ranks, a leader

Many patrons of Milwaukee’s Potawatomi Bingo Casino enter the building through the parking garage’s skyway, where an escalator delivers them to the gambling floor. It’s a descent into chaos: blinking and flashing lights, cigarette smoke, the hustle of bodies and the din of a thousand bells and sirens signaling victory or defeat.

Just off the casino floor is RuYi, one of six restaurants in the building. In its kitchen, a diverse team of cooks toils to bring authentic Asian cuisine to life. “Authentic” isn’t a platitude here; these young cooks are Burmese, Chinese, Japanese, Hmong, Filipino, Thai, African American, and Native American. They are led by two chefs who have developed a graceful harmony over six years working together.

Head Chef Tony Ho and Sous Chef My Ong “Mo” Vang were paired to run RuYi by Potawatomi’s Executive Chef Peter Gebauer, who saw in them the kind of potential for synchronicity and growth that so often defines the success of any food-centric business.

“From day one, I was trying to create a culture focused on change and education,” Gebauer explained. “In the case of RuYi, Tony is a role model for one-on-one coaching and mentoring, but Mo is becoming even better and more proficient at leading people than he is.”

To pair formal training with mentorship, Gebauer established The Culinary Academy at Potawatomi, which he likens to an apprenticeship. The self-paced program includes 31 classes taught weekly by senior chefs, and offers certifications at multiple levels. To date, 335 cooks and stewards have completed the courses, including Vang, who is the only sous chef to ever serve as an instructor.

An ethnic Hmong who emigrated from Thailand at age 2, Vang worked hostess and other front-of-house jobs in the city for many years, but always dreamed of having her own place.

After completing a program at Milwaukee Area Technical College, she began cooking for Potawatomi’s Buffet in 2007. She excelled early, and was promoted within her first year. Then she got word that the casino was opening an Asian restaurant concept as part of its 2008 expansion.

“I talked to Chef Peter and said ‘this is where I want to go. This is where I want to be,'” she recalled. “He told me to see Chef Tony and we’ve worked together ever since.”

Ho was born in Hong Kong and moved to Japan in his teens, working in an Italian restaurant in Tokyo. At 22 he emigrated to the U.S. and settled in Chicago, where he began a 17-year career cooking for Hyatt hotel properties in Chicago, Manhattan, Malibu and Oklahoma City. He then ran his own restaurant in Kansas City for 15 years, sold it, moved to Milwaukee, and started working at Potawatomi, first at Solstice, then RuYi.

“Chef Tony is kind of old school in his upbringing and how he was taught,” said Vang. “For Asian Heritage Day we made a bunch of dishes for the staff and we had chicken feet up there. Most people weren’t into it but he was like, ‘What’s the big deal?’ He has so many skills; you can put anything in front of him and he can make something out of it.”

She added that while Ho is a technically proficient chef, she likely possesses more ‘soft’ skills. “His strength is in teaching how to do something; mine is in translating why we do it that way. It’s a give-and-take relationship.”

Ho speculated Vang’s ability to be an effective instructor in the kitchen surpasses even his own.

“Chef Peter saw that Mo had talent,” he said. “She’s smart, particular, and has a good personality. He knew she could be a leader. The way she approaches people makes you feel very warm and comfortable. She’s far better than me at training people and showing them how to do something.”

“I have eyes behind my head, and my ears are always open,” Vang said in affirmation. “I teach our guys to always be aware, because there are safety issues. A fire can start in a wok just like that. It’s happened. ‘Fire! You didn’t see that?!’ So we work on awareness because of how we cook.”

Guidance toward excellence is an ever-present part of life in the RuYi kitchen.

“It’s a reward for me to help these guys the way Chef Tony helped me,” said Vang. ” We want our people to become so successful that if they were to become our bosses one day, it would be an honor.”

Ho said the toughest thing to teach Vang was to take the time to understand the intent behind the words he or others spoke.

“English isn’t my first language, and I’m used to communicating in Chinese or Japanese,” he said. “Sometimes when I speak out from my heart, something might be lost in translation and it can cause small problems. But we always work it out quickly. She’s my right-hand person. Left and right hand.”

“My mother told me my whole life to be patient,” Vang said. “In Hmong, patience is ‘saib ntev’ which means ‘long heart’ or ‘patient heart.’ It wasn’t until a couple of years ago that I finally got what it meant. I have a son who’s 19 now, so me having to be his teacher his whole life is part of the process of learning patience. I got it because I feel it, and I live it here every day.”

The shepherd leads a flock

As cheesemakers go, Bob Wills is a rock star. One of more than 50 master cheesemakers in the state and owner of Cedar Grove Cheese in the town of Plain outside Madison, as well as Clock Shadow Creamery in Milwaukee’s Walker’s Point neighborhood, Wills has trained more than 60 cheesemakers over the past two decades.

He’s also something of an enigma. With a Ph.D. in economics and a law degree from the University of Wisconsin, he stumbled into the cheese business in 1989 quite by accident, when he quit his job as an economist for the U.S. Department of Agriculture to marry a longtime cheesemaker’s daughter and settle into the family business started in 1878.

Wills learned the craft of cheesemaking from his father-in-law, Ferdinand Nachreiner, who had made cheese for 50 years. His tutelage, coupled with that of Dan Hetzel, who worked at Cedar Grove for 52 years (until 2010), was critical to the neophyte overcoming a steep learning curve.

“My ignorance was immense,” he said of his initial knowledge. “Cheesemaking is a combination of art and science. The artistry is something you can’t pick up in a book, so these guys with all this experience probably couldn’t have passed the Master Cheesemaker exam, but they could make amazing cheese day after day after day. I’m still in awe of their skills.”

Over years honing his craft, Wills became the man people turned to when trying to get a start in the cheese business. He played a key role in the genesis of nearly a dozen cheese brands, including the most-awarded cheese in American history, Pleasant Ridge Reserve, crafted today by Andy Hatch of Uplands Cheese.

The only cheese ever to have won both Best of Show in the American Cheese Society’s (ACS) annual competition (three times) and the U.S. Cheese Championships (once), it was produced at Cedar Grove’s facilities for the first four years of its illustrious life, before then-owner Mike Gingrich built his own cheese plant in 2004.

“Bob really stirs the pot when it comes to other cheesemakers,” said Steve Ehlers, owner of the artisan cheese and specialties shop Larry’s Market in Brown Deer. “So many cheesemakers in this state came to him to get their start because he’s so collaborative and smart and he wants to empower people who have a passion for learning the business.”

Pleasant Ridge Reserve is just one of many award-winning cheeses Wills had a hand in. For instance, at the 2008 ACS competition, 14 of the 91 awards given to Wisconsin cheesemakers were won by artisans mentored by Wills, or by cheeses made at Cedar Grove.

“My cheesemakers become better at what they do by having exposure to really creative people and by trying new things and learning what happens,” said Wills.

Despite the accolades, Wills remains focused on maintaining high quality, as well as creating new cheeses and new ways of bringing them to market.

“Some things are just opportunities you see and grab. There was never a plan to open a cheese factory in Milwaukee, and there was never a plan to make water buffalo cheese, but we said ‘Let’s do this.'”

In addition to selling its products, which include cheese curds, mixed-milk cheeses, quark, chèvre, Latino cheeses and more in the retail space adjacent to its processing facilities, Clock Shadow Creamery sells wholesale to retailers and restaurants.

Ron Henningfeld, lead cheesemaker at Clock Shadow, was a high school teacher looking for a career change when he met Wills, who took him in at Cedar Grove’s plant in Plain, then loaned him out to Uplands Cheese before sending him to Milwaukee to help set up operations and oversee construction of the creamery.

“Ron is dependable and great with people, but he’s also very careful,” said Wills. “He doesn’t make dumb mistakes, and he’s very focused on the safety aspects of cheesemaking, which is vitally important for the reputation of the business.”

Not making dumb mistakes is crucial because bacteria from an improperly made batch have the potential to kill, said Wills. When mentoring cheesemakers, he stresses attention to detail, understanding nuance, and an ability to react – qualities hard to teach but important to nurture.

“Every day is a little bit different, he said. “The temperature in the plant, the food the cows have been eating, how the weather affected them, how much water they drank – everything changes. So you can’t use a recipe or formula and expect everything to work out. You have to be able to recognize what’s happening and make adjustments as you go.”