The Settlement Cook Book

Lizzie Black Kander and the Way to Milwaukee’s Heart

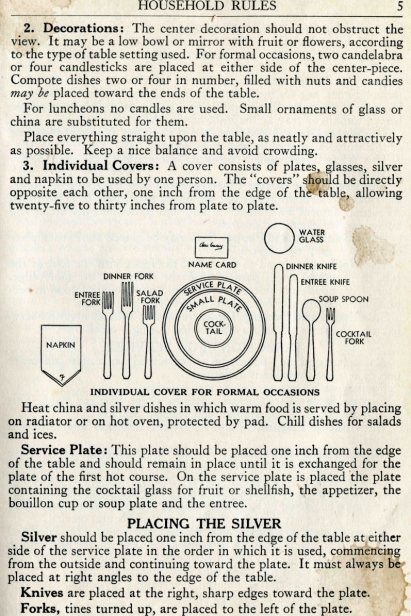

Many of us grew up with it in our homes. American chef and food icon James Beard called it one of his favorite cookbooks. It offered counsel: “The table should look as neat and attractive as possible. Place everything straight upon the table. Turn no dishes upside down.” Lizzie Black Kander’s The Settlement Cook Book: The Way to a Man’s Heart provided recipes for the kitchen and the ingredients for American life.

But where the title may have meant little to many of the book’s fans, for people in Milwaukee, the book’s title recalled a real place. The Settlement, and its successor, the Abraham Lincoln Settlement House, taught generations of Jewish immigrants middle class values, foods, and customs.

“Growing up in Tennessee, we had the cookbook in the house, as did my grandparents, but I didn’t realize where it came from until I moved here and started looking for recipes,” says Ellie Gettinger, education director at the Jewish Museum of Milwaukee. “The cookbook is really national, but the story behind it—the woman behind it—is uniquely Milwaukee.”

Kander has been called the “Jane Addams of Milwaukee” after the famed founder of Chicago’s Hull House, but the comparison is inexact. Kander never lived in an urban slum or collected scientific data. She was older than Addams, Jewish, married, and financially secure. Kander felt a responsibility to serve the less fortunate and stayed close to home to do so. She understood that food could be a powerful means of cultural expression and grounded her efforts in the stovetops and ovens of her hometown.

Born in Milwaukee on May 28, 1858, Lizzie Black Kander grew up in one of the city’s founding families of the local Jewish Reform community, which worked to reconcile religion with progressive ideas. Kander’s mother instilled in her daughter a deep appreciation of a domestic education. But an education at home didn’t preclude formal schooling. Kander was named the valedictorian of her class at Milwaukee East Side High School in 1878. Her valedictory speech, “When I Become President,” audaciously criticized suffragettes for complaining about men’s abuses of their rights. She urged women to put their natural maternal and moral skills to work remedying social ills. With such a speech, it’s perhaps not surprising that she spent much of her life working with and for the city’s poor and immigrant communities.

“She was an early and firm believer that you just help because it’s the right thing to do,” says Traci Nathans-Kelly, a culinary historian with a special interest in community cookbooks.

After graduation, Kander joined the Ladies Relief Sewing Society, an organization charged with seeing to the needs of Milwaukee’s expanding population of immigrant families. She also became involved in school reform where she met her husband, Simon Kander. The two married in 1881. They had no children of their own, but Kander devoted much of her life to work with young people.

In 1898, Kander began offering cooking classes to girls at the Milwaukee Jewish Mission. The organization merged with another Jewish charitable group, the Sisterhood of Personal Service, in 1900 to become The Settlement, Milwaukee’s first multipurpose reform organization.

Settlement houses were important reform institutions in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. They provided services such as daycare, education, and healthcare to residents in low-income, usually immigrant, neighborhoods.

Kander served as president of The Settlement for nearly 18 years. As president, the Settlement’s programs and continued existence depended on Kander’s ability to raise funds. Her cooking classes were among the institution’s most popular activities. Students wasted a lot of class time copying recipes from the board, so she suggested publishing a charitable cookbook as a time saver for her students and a fundraiser for the organization.

Kander took her idea to the Settlement’s Board of Directors and requested $18 to print the cookbook. The all-male Board balked at the cost, declaring the book an “extravagance.” Kander refused to be deterred, however, and succeeded in raising funds for the book’s publication through advertisements. The first edition of The Settlement Cook Book was published in 1901 and included recipes and housekeeping tips, as well as ads for Adolph Ahrler’s Confectionary Delights and Charles Ludwig’s Hamburg Sausage.

What the book didn’t contain was many kosher recipes. Kander likely assumed many of the immigrants already knew how to cook kosher. “It was typical American fare that was a mystery to them,” says Nathans-Kelly. “That is what the book was meant to cover for her classes.”

The book included foods from many nations and ethnicities. Early editions had recipes for spatzen, hasenpfeffer, “spaghetti Italienne,” and a Turkish pilaf. Milwaukee journalist Tillie Goldstein recalled Kander inviting her mother and other community women to cook their favorite delicacies while volunteers from The Settlement watched and compiled recipes from the dishes the women made by instinct. These recipes became part of the cookbook. The book also taught users how to entertain like an American with recipes for cocktails, instructions for the use of a fish knife, and how to make lemonade for 150 people. It was unlikely that the young working class women in Kander’s classes would ever have a staff or need for these skills.

The first edition—1,000 copies—sold out quickly. Kander saw her book as a work in progress and founded The Settlement Cook Book Company to deal with subsequent editions and the disbursement of profits. She carefully edited each edition, reorganizing content and making adjustments to correct errors. She also incorporated the latest kitchen technological innovations and cultural fads. Kander oversaw the revision of 23 editions.

“It’s amazing to me that she edited each version of the book until her death. Kander’s hand is in all of those early books. Each one!” exclaims Nathans-Kelly.

During the succeeding decades, the book went on to sell more than 1.5 million copies worldwide. The little cookbook from Milwaukee became a national sensation.

Kander’s work wasn’t entirely altruistic. Central to her work was the perception that poor immigrants would tarnish the reputation of more established German Jews in Milwaukee. She hoped that encouraging immigrants to embrace self-reliance, cleanliness, and American-style cooking would uplift them all and stave off anti-Semitism. It was a viewpoint common to Progressive era reformers.

“The Americanizing impulse may not have come with pure motivations but Kander’s devotion to her cause and her work ethic cannot be underestimated,” says Gettinger.

Nor can the impact Kander’s teaching had on the women she taught. In 1914, local woman Rose Sosoff carefully transcribed lessons straight from Kander’s book for such things as Dutch Apple Cake, Corn Chowder, and Pea Soup. Women like Sosoff appreciated the education and saw it as their ticket to an American life. Goldstein called The Settlement a way for “foreigner women” to “learn the language and to become Americans, so that they could keep up with their yankee doodle children.”

Royalties from the book supported everything from hygiene classes to bathing facilities and English-language instruction. The cookbook paid for the construction of a new building, the Abraham Lincoln Settlement House in 1910 (Kander refused to allow the building to be named in her honor), and the Jewish Community Center of Milwaukee in 1931.

Kander’s community engagement extended beyond the doors of The Settlement. During World War I, Kander headed Milwaukee’s Food Conservation Council and provided instruction on preserving and cooking without rationed foods like meat, wheat, and sugar. From 1909 to 1919, she served on the Milwaukee School Board, helping to establish the Girls Technical High School, which provided vocational training to young women. She hired women to cook large quantities of food that they sold at a low price during the Depression. She also wrote a regular cooking column for the Milwaukee Journal.

And yet the woman behind the book is little known today. Women who write cookbooks aren’t usually the stuff of history textbooks—even women like Kander. It is, unfortunately, easy to miss the stories of women who worked for the benefit of their own communities. But cookbooks do matter, offering a window into home life—or at least, the ideals of home life—and what’s important to a community.

The state of Wisconsin honored Kander in 1939 as one of the state’s outstanding women, and in 1951, the Wisconsin Historical Society selected The Settlement Cook Book as one of the most influential of their library’s 3.6 million titles.

“The Settlement Cook Book is a cornerstone of American cooking,” says Nathans-Kelly. “To me, Kander and her work through the art of cooking deserve more attention. The link that she drew between food, culinary skills, language, and political life for women is absolutely fascinating.”

The Settlement Cook Book continues to inspire great devotion, each edition a prized possession, for the changes and time reflected in its pages.

“Kander was so dedicated to her community and did so much with what was available to her,” says Gettinger. “Her book achieved cult status because it wasn’t just a cookbook, but a guide to life in America.”

Illustrations from The Settlement Cook Book