Victory Gardens in Wartime Wisconsin and Today

Patriots plant plots and gardeners move grass to feed selves, community

Meatless Mondays aren’t new. Nor is eating less wheat or raising backyard chickens. One hundred years ago, on the World War I home front, the shovel became a rifle and the furrow a trench. “Every gardener in the land has a part to take in the fight! His duty awaits him just as certainly, and, if anything, more imperatively, in the rows of vegetables in his garden, as does that of the soldier in the trenches at the front,” proclaimed the Sheboygan Press in 1918. “The gardener who does not plan his garden well, who fails to plant the right kinds of vegetables, who neglects his garden after it is planted, is a Slacker.”

No one wanted to be a slacker.

Food was the principle weapon against the Hun, as Americans were urged to save wheat, sugar, fat, and meat to feed the Allies. In support of the war, Americans filled their plates with dogfish, sugarless candy, whale meat, rye and corn bread, and horse steaks. They learned to prize leftovers nearly as much as the original meal.

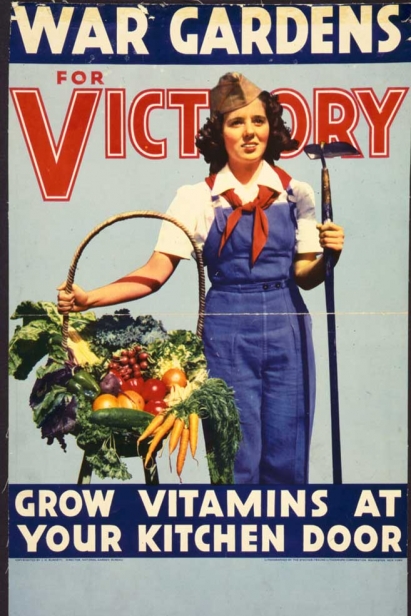

And Americans planted gardens. A war garden was a home garden that increased local food production and freed up resources for American and European soldiers. Growing vegetables became patriotic during the war and millions of Americans joined in, waving spinach along with their flags. President Wilson even grazed sheep on the White House lawn. Everyone was urged to do his or her part.

The outbreak of war brought tremendous shortages of food across Europe as farmers put down their plows and picked up their rifles, fields of food becoming fields for battle. By the time the United States entered the war in 1917, three years of fighting had seriously damaged European supplies. U.S. entry into the war only further disrupted the supply of food.

As an agricultural state, Wisconsin took a keen interest in the food crisis. State Council of Defense Chairman Magnus Swenson of Madison began promoting food conservation before Congress had even created the United States Food Administration to do the same nationally. In Wisconsin, Swenson attacked food hoarding, urged citizens to cultivate backyard vegetable gardens, and instituted “meatless” and “wheatless” days. Wisconsin was also the first state to form a State Council of Defense, the primary vehicle for implementing, supervising, and regulating war activities on the state level. So impressed with Swenson and Wisconsin’s efforts that when President Woodrow Wilson put Herbert Hoover in charge of the newly created the Food Administration, Hoover adopted many of Swenson’s policies. He also took to Swenson’s model of making women, gardens, and kitchens the first line of defense on the home front.

Swenson first tackled food waste. He reduced fire hazards at grain elevators, warehouses, and other places where food was stored. He worked with researchers at the University of Wisconsin to promote high-yield, disease resistant crops. He urged taverns to stop serving the traditional free lunch and commissioned scientists to study the health benefits of stale bread.

With so many men at war, farm labor was in short supply. Automobile squadrons transported older men and young boys out to farms to harvest crops so that nothing would go to waste. So they wouldn’t be a burden to farm wives, the men carried their own lunches.

With trucks and trains needed to transport soldiers and supplies, Americans were urged to plant gardens. War gardens were the brainchild of forester Charles Lathrop Pack and his National War Garden Commission. At his urging, gardens “sprang up as though by magic.” Gardening, proclaimed Pack, “came to be a thing,” with people from all backgrounds and no experience joining in. Americans planted vegetables in their yards but also in window boxes, vacant lots, and on rooftops. The Milwaukee Agricultural Commission gave away 11,000 packets of seeds, 9,000 tomato plants, and 14 bushels of potatoes. They distributed thousands of leaflets with basic gardening information. Women could also attend classes on canning and food preservation provided free of charge by University of Wisconsin Extension agents. Leftover produce was canned and distributed to people in need.

Women joined the war effort without ever leaving the kitchen. Meatless and wheatless days became the centerpiece of Swenson’s food plan. Soon, the whole country joined in.

In the kitchen, women learned to use corn and rye instead of wheat, chicken instead of beef, and to cook more vegetables. They signed pledges promising to reduce waste and conserve muchneeded war foods. More than eighty percent of the women in Milwaukee County signed on. The Women Students’ War Work Council and the UW Home Economics Department produced a wartime recipe booklet to show how easy it could be to cook with alternative ingredients. Recipes included steamed barley pudding, scalloped cheese, liver pudding, and something called “salmon box”—a loaf pan lined with rice and filled with cold, flaked salmon.

Meatless and wheatless didn’t just apply to home-cooked meals. Restaurants were also encouraged to adopt conservation menus. Many printed American flags under the section of the menu usually listing roasts and other main dish meats.

Even children were targeted with conservation messages. Children signed their own special Junior Soldier Flag Pledge cards, admonishing them to conserve and to convince their parents to do the same. In school, kids found posters proclaiming the virtues of potatoes while their teachers read them conservation fairy tales like the Fairy Story on Potatoes to encourage more potato consumption. Students in the Liberty Bread Club at one Waukesha school vowed, “I pledge my head, my heart, my hands, and health for the conservation of food to win the world war and the world peace.”

While meatless and wheatless days may have involved some form of sacrifice, it wasn’t all that bad. Meatless meant no beef or pork—chicken and fish were okay. In fact, Americans were urged to raise their own backyard poultry flocks. A meatless menu offered on the Chicago, Milwaukee, and St. Paul Railroad, for example, included a half a chicken and shredded crab on toast.

When the fighting finally ended in late 1918, Americans had shipped nearly 10 billion pounds of meats, fats, dairy products, wheat, and vegetable oil overseas. Wisconsin increased its food production by 25% while sending 50,000 farmers to war. The state led the nation in conservation of wheat and meat. Perhaps most remarkably, all of these conservation programs were voluntary. No one had to join in (though they faced tremendous peer pressure to do so) but millions did.

The nation again turned to conservation and gardening during World War II but this time, Americans received ration books limiting what they could buy. Many of the programs pioneered during the first World War were repeated in the 1940s. Gardening had never really gone out of fashion. During the Depression, community plots provided a place for the unemployed and poverty-stricken to grow food. At its peak in 1944, the United States had more than 20 million gardens producing 40 percent of all vegetables grown in the United States. Among the new vegetables popularized by war gardens were Swiss chard and kohlrabi, in part, because they were easy to grow.

Despite such momentum, though, backyard and community gardening lost steam when the troops came home. Many Americans associated victory gardens with deprivation and hard times, and they felt liberated by the convenience foods that made gardening unnecessary.

But home gardens have come back in a big way in recent decades, though the battle has changed. Rather than Germany and her allies, today’s urban gardeners are fighting for food security, local economies, and their communities.

“People really care about food and health,” says Gretchen Mead, executive director of Milwaukee’s Victory Garden Initiative. “Everyone has an ‘in’ to the food movement. We’re all stakeholders because we all eat and most of us want to eat good food.”

Mead began growing food in her own front yard in Shorewood in 2008. Not everyone supported her choice. Some neighbors protested her front yard garden, preferring manicured lawns to tomato cages, but Mead felt compelled to act, caring more about what she felt was right than what her neighbors thought. A clinical social worker by training, Mead had seen the impact of the growing disconnect between people and healthy food on her patients’ health. She founded the Victory Garden Initiative in 2008 to change the food system by removing the barriers to growing food.

“I met more people through my garden,” says Mead. “Food serves the purpose of a front porch, bringing people together and creating community. Some people didn’t like it but I got mostly positive feedback and more people started growing their own food.”

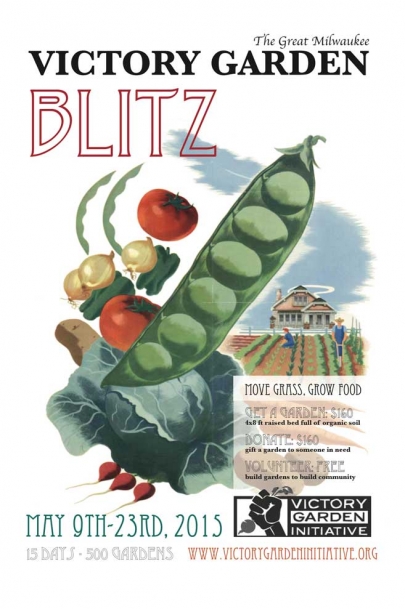

Energized, Mead and her supporters launched a Victory Garden Blitz in 2009, planting 35 new gardens in a single day. In 2014, volunteers and staff built nearly 550 gardens over two weeks. Interested participants register to receive gardens during the Blitz. The group also works with community organizations to identify people who might want a garden. The hope is to provide at least half of the gardens to low-income families. New gardeners can receive help from a garden mentor, not unlike the assistance provided by extension agents and women’s groups during the wars.

“People were motivated by a higher good during the world wars,” says Mead. “They were helping the war through food.”

Excess food is also finding a home in Milwaukee, just as it did during the wars. Glendale-based Tikkun Ha-Irruns a Surplus Harvest Food Justice Initiative that collects remaining food from farmers markets, CSAs, farms, orchards, and home and community gardens. The food is then distributed to homeless shelters, food pantries, meal sites, veterans’ organizations, and to others experiencing hunger. Like the Victory Garden Initiative, Tikkun Ha-Ir strives to increase access to fresh food.

For Mead, the Victory Garden Blitz is not just about growing food, but about building communities. Mead herself grew up in northwestern Illinois in a self-sufficient household, eating vegetables from the garden and wild game. She found city life hard when she moved to Milwaukee for graduate school. She longed for open space and fresh food. But like the people she helps plant gardens, Mead fell in love with Milwaukee and found kinship through vegetables.

“We say the “Blitz is a gateway to gardens” but it’s also a gateway to engagement and inspiration,” explains Mead.

To that end, the Victory Garden Initiative also trains people in community organizing and urban agriculture as part of its Food Leader Certificate Program. These leaders go on to bring people together around food in their own neighborhoods.

Community played a central part in the gardens of the World Wars, too. “Probably nothing is more potent as a factor for building community spirit than gardening,” proclaimed Charles Pack in 1919. “It unites all hands in the common end of producing food. Rubbing elbows in their garden patches, lawyers and laborers, tradesmen and housewives, speedily discover they have much in common.”